Every church Flourishing Episode 3 Re-Edit, 02/03/2026.

Every Church Flourishing Episode 4 Re-Edit 02/04/2026.

Every Church Flourishing episode 5, Re-Edit 02/06/2026

Roger Williams and Church-State Relation Controversy in Colonial America

Modern American Christians have a romanticized view of our country’s religious history. Many think that the men and women who populated the early colonies, fleeing religious persecution in strife-torn, Bible-deviating Europe, were paragons of virtue and got along famously with each other and the Native Americans they encountered. I hate to pop your idealistic history bubble, but the reality is quite different. Early Colonial Christians did indeed escape religious controversy and persecution in the Old World, but they also quickly instigated their own religious controversies and persecutions in the New World. Today we are going to take a look at the stormy history of Roger Williams – a Baptist pioneer, founder of Rhode Island, Native American linguist, prolific author, polymath, pastor, law reviser, Commissioner to run the Eastern Line, Commissioner to Settle Difference with Connecticut Colony, and the first Guinness Book of World Record holder for number of times banished from a colony in the New World. (1.) You see, it wasn’t just Europeans that expelled people for religious differences…early Americans, pre-Founding Fathers, did the same exact thing. Indeed, as Elisha Reynolds Potter notes, Ann Hutchinson, French Protestant Huguenots, and Roger Williams were all expelled by the Christian founders of Massachusetts and ultimately found a home, for a time, in Rhode Island. (2.)

Williams wrote extensively on church-state relations, and a religious liberty philosophy remarkably like that of Williams would eventually become enshrined in the United States Constitution, with Thomas Jefferson borrowing Williams’ analogy of separating church and state over one hundred years after Williams first used it. In many people’s minds, the colonial understanding of the separation of church and state refers to the necessity of keeping the influences of religion out of all government activities, but neither Williams nor Jefferson advocated for a government free from religion. (4.)

Exemplary of his tendency to court controversy, in 1632, Williams wrote a pamphlet that was critical of the Plymouth Plantation’s charter, issued by King James, on the grounds that the English had no right to grant territory owned by Native Americans. (5.) John Winthrop’s journal records the circumstances of Williams’ censure, noting that the “magistrate and ministers” all judged Williams' views to be “erroneous and very dangerous,” and a “great contempt to authority.” (6.)

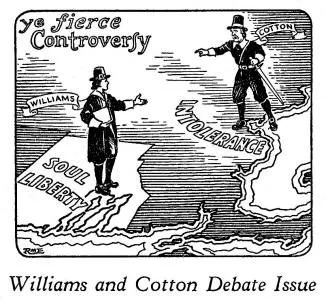

William’s experience of banishment, criticism, and censure from colonial Christian leaders fueled his later extensive writings on church-state relations and religious liberty, and he quickly became an antagonist to many New World Puritans and those who tried to maintain strict unanimity in the Colonies. His works, advocating for freedom of religion and contending against government-enforced religious doctrine, were quite controversial for his day, and brought him into an extended ideological dispute with Puritan minister John Cotton.

James Davis Knowles recounts this dispute in his editorial comments found in Roger Williams’ memoirs, noting that the two pastors wrote long book-length arguments back and forth with each other, contending and debating various fine points of religious liberty. Generally speaking, Cotton favored a strong government that backed up and enforced decisions of the church, whereas Williams argued for a “wall of separation” between government and church whereby neither one dictated to the other. (7.) Neither Cotton nor Williams admitted defeat to the other, but it is quite clear that Williams’ understanding of church-state relations ultimately prevailed over that of Cotton. These exchanges, chronicled extensively through pamphlets and letters, reveal the intense intellectual and theological battles that shaped early American religious thought. Far from a paradise of unity and gentility, the landscape of early American theology and ecclesiological disputes was just as stormy as that of Europe.

1. Roger William’s jobs, other than that last one, are found listed in the Civil and Military List of Rhode Island (in the Sabin America Database) Joseph Jencks Smith, Civil and Military List of Rhode Island, 1647–1800: A List of All Officers Elected by the General Assembly from the Organization of the Legislative Government of the Colony to 1800 (Providence, RI: Preston and Rounds Co., 1900), 14, Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500–1926, accessed May 30, 2025, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0107657121/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=dc502bf2&pg=14.

2. Elisha Reynolds Potter and Rhode Island Historical Society, An Address Delivered before the Rhode-Island Historical Society: On the Evening of February Nineteenth, 1851 (Providence, RI: G.H. Whitney, 1851), 5, Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500–1926, accessed May 30, 2025, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0108282666/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=bad5190d&pg=5.

4. As Williams contends in his dense and difficult to read colonial prose, “First the faithfull labours of many Witnesses of Jesus Christ… abundantly proving, that the Church of the Jews under the Old Testament in the type, and the Church the Christians under the New Testament in the Antitype, were both separate from the world; and that when they have opened a gap in the hedge or wall of Separation between the Garden of the Church and the Wildernes of the world, (When Gods people neglect to maintain that hedge or wall, God hath turned his garden into a wildernesse.) God hath ever broke down the wall it selfe, removed the Candlestick, &c. and made his Garden a Wildernesse, as at this day. And that therefore if he will ever please to restore his Garden and Paradice again, it must of necessitie be walled in peculiarly unto himselfe from the world, and that all that shall be saved out of the world are to be transplanted out of the Wildernes of world, and added unto his Church or Garden.” Williams’ “wall of separation,” as explained in this passage, does not advocate for limiting church activity relative to the government, but rather limiting the incursion of the secular values and mindset of the world into the church, lest the church lose its lampstand, or spiritual life and vitality, and revert to being wilderness, instead of a garden. Quote from: Reuben Aldridge Guild, ed., Letter of John Cotton, and Roger Williams’s Reply, vol. I, Publications of the Narragansett Club (First Series) (Providence, RI: Narragansett Club, 1866), 108.

5. A very revolutionary and forward-thinking idea for the 17th century! Jimmy D. Neff, “Roger Williams: Pious Puritan and Strict Separationist,” Journal of Church and State 38, no. 3 (1996): 529–46, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23920083.

6. John Winthrop, The History of New England, 1630–1649, ed. James Kendall Hosmer (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), 154.

7. Knowles, James Davis. Memoir of Roger Williams, the founder of the state of Rhode-Island. Boston: Lincoln, Edmands and co., 1834. Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926 (accessed May 30, 2025). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0100831038/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=48d803cb&pg=197.